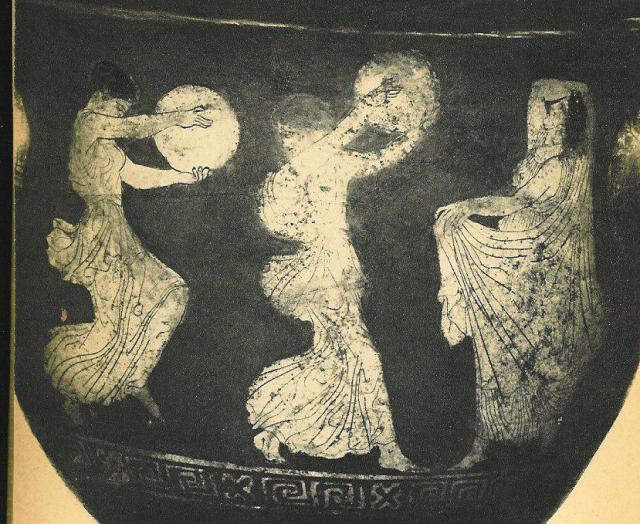

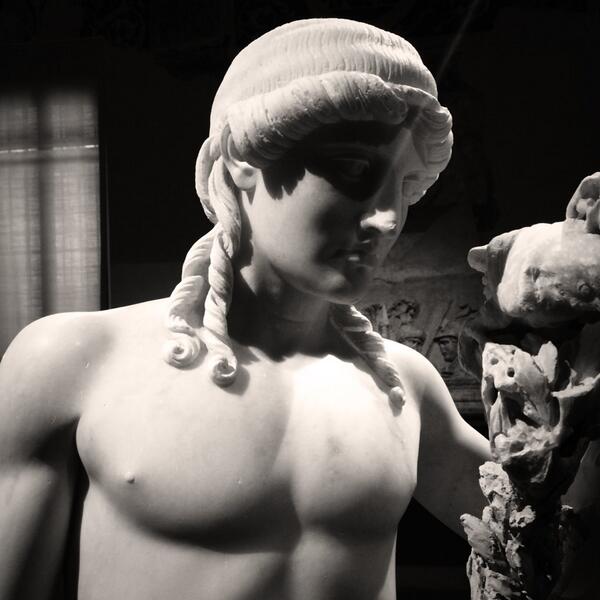

“Summer,” terracotta via http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/207350?utm_source=Pinterest&utm_medium=pin&utm_campaign=summer

1.“I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,

Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,

Quite overcanopied with luscious woodbine,

With sweet musk roses and with eglantine.

There sleeps Titania sometime of the night,

Lulled in these flowers with dances and delight.

And there the snake throws her enameled skin,

Weed wide enough to wrap a fairy in.”

William Shakespeare, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

2.“…he drank a bottle of the scent of a summer evening, imbued with perfume and heavy with blossoms, gleaned from the edge of a park in Saint-Germain-des-Pres, dated 1753.”

Patrick Süskind, “The Perfume”

All color flowers in full bloom, canopy of leaves, carpet of grass, bees swarming, the sun oozing heat lavishly – wherever I look, I see bountifulness, I feel how life peaks in me, but how also summer weariness and sweet sensual confusion descend upon me. I am all smell. That reminds me of Christopher Moltisanti, a character from “The Sopranos,” who said he “got high off the smell of popcorn at Blockbuster.” Well, I do find all the collective aromas of the summer intoxicating; I keep catching myself wanting to smell everything around me, whilst imbibing on the hot air. I pick up The Healing Power of Trees: Spiritual Journeys through the Celtic Tree Calendar by Sharlyn Hidalgo, which is one of those effortless reads that keep me nodding and smiling lightly all the time. “I want to be able to understand the novel half-drunk on rosé,” wrote a critic from The New Yorker in an article recommending perfect summer reads. This is it but without losing the depth. Hidalgo’s book is not a scholarly work, but it does have enormous spiritual scope, lots of intuitive wisdom and was written with a true passion for the subject.  I appreciate her ability to weave together various cultural traditions such as Celtic, Greek and Egyptian myths, astrology and the runes. Recently, the most exciting plant I have been checking upon in my immediate neighborhood has been the vine (below is a low-quality amateur snapshot I took of it).

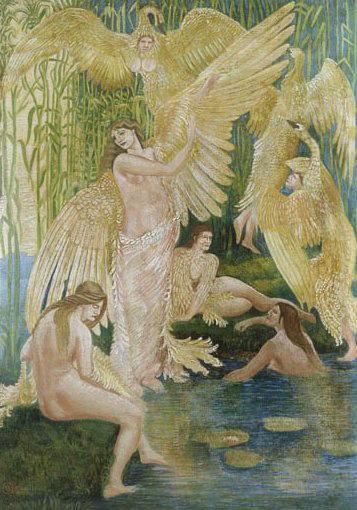

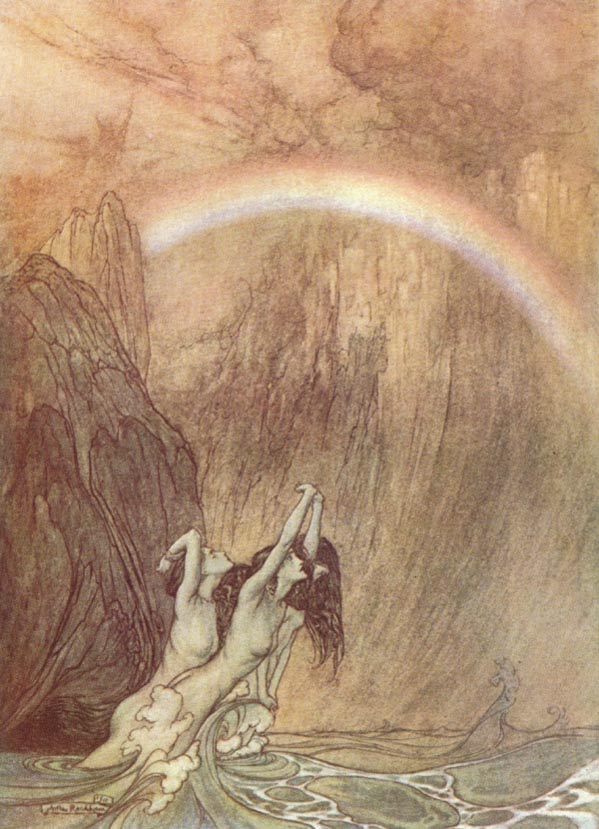

I appreciate her ability to weave together various cultural traditions such as Celtic, Greek and Egyptian myths, astrology and the runes. Recently, the most exciting plant I have been checking upon in my immediate neighborhood has been the vine (below is a low-quality amateur snapshot I took of it).  According to Hidalgo, on 11 July Celtic month of the vine started and will last until August 7. The guides and totems of this month are Lion, Dionysus, the Green Man, Pan, sylphs, nymphs, elves and fairies, the sun god Lugh, Strength card of the tarot, Sekhmet, Kuan Yin, and all mother aspects of the goddess (mother earth offering her bounty for the harvest).

According to Hidalgo, on 11 July Celtic month of the vine started and will last until August 7. The guides and totems of this month are Lion, Dionysus, the Green Man, Pan, sylphs, nymphs, elves and fairies, the sun god Lugh, Strength card of the tarot, Sekhmet, Kuan Yin, and all mother aspects of the goddess (mother earth offering her bounty for the harvest).

Martin Schongauer (German, c, 1435/50-1491), Shield with Stag Held by Wild Man. Engraving. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

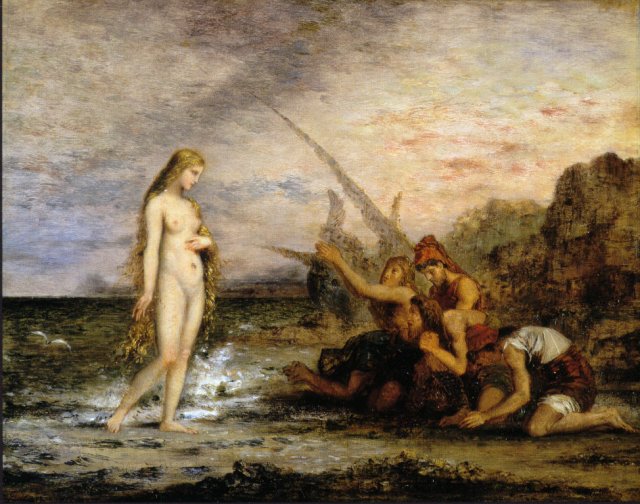

A few glasses of wine bring a feeling of warm gregariousness, loosen ego boundaries, open the heart and endow with a feeling of expansiveness. In a further stage, imbibing on wine may result in ecstatic frenzy, in the likelihood of the female followers and priestesses of Dionysus – the Maenads, whose name signified “the raving ones.”

Wine brings forward the deepest emotions by dissolving the boundaries that hold us back from full self-expression. Hans Biedermann writes this on the symbolism of wine in his Dictionary of Symbolism:

“The custom of intemperate drinking, in various cultures that revered Dionysus, was part of a religious tradition and was believed to join mortals with the god of ecstasy. Wine supposedly could break any magic spell, unmask liars (“in vino veritas”), and slake the thirst even of the dead when it was poured out as a libation and allowed to seep into the ground. Called ‘the blood of the grape, wine was often closely linked symbolically with blood, and not only in the Christian Eucharist. Poured out as a libation, it could replace blood sacrifices for the dead.”

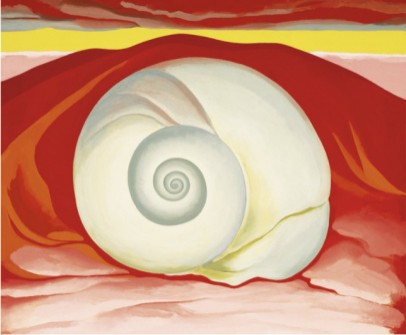

In John’s gospel, the very first miracle Christ performs was turning water into wine. This miracle underscored the ambivalent significance of wine, as Juan Eduardo Cirlot in his Dictionary of Symbols aptly noted, wine pertains both to fecundity and sacrifice. It is a symbol of life in its fullness, and life in its fullness must encompass death and suffering. The vine will not produce good quality wine without ample sun: almost no other plant channels the vigor of the sun in such a marked way. But the height of the summer carries the seeds of death within, symbolized by the harvesting scythe. Sharlyn Hidalgo writes:

“The idea of the sacrament of the last supper of Christ was originally a Dionysian ritual wherein women ate a piece of bread shaped like him (representing his body) and drank wine (his blood). Through this ritualized consumption, the women took in and absorbed the wild, potent power of nature. The ancient Greeks used tools resembling T-squares to cultivate grapevines. Later, these Tau crosses morphed into the structure adopted by the Romans for crucifixion.”

Quite a free leap in associations, but I appreciate it. Christ said of himself that he was the vine, while his disciples were the branches. He was the one who gave life to his followers. He poured his divine substance into them. In medieval art, the cross and the tree of life were both represented as grapevines. Saint Hildegard von Bingen said that wine was endowed with the mysterious and secret vital force (viriditas). The poet Dylan Thomas understood viriditas perfectly, because he knew that life force and death force are essentially the same; in one of his most wonderful poems he wrote: “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower/Drives my green age;/ that blasts the roots of trees/ Is my destroyer.”

From the point of view of the soul, the miracle work of wine endows us with wings of fertile creativity. This creativity sometimes seeks to destroy, for example by dissolving any boundaries or barriers in order to claim a wider territory on grounds of the psyche. The creative spirit of the season was best captured by the genius of Shakespeare in his Midsummer Night’s Dream:

“Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover and the poet

Are of imagination all compact:

One sees more devils than vast hell can hold,

That is, the madman: the lover, all as frantic,

Sees Helen’s beauty in a brow of Egypt:

The poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.”

I remember seeing it many years ago in the theater and being completely overpowered by its Dionysian message of loosening of boundaries, and an invitation to unbridled revelry. I remember being struck by the impression that I was being exposed to an unlimited geyser of creative force. Summer is often the time taken off from our everyday, constraining social roles. As the character in Shakespeare’s play, we are invited to frolic around in the woods governed by freedom giving divine laws of the fairies.